Space Invaders

Summary: Living in the natural world and early and recent video game experiences.

I was 5 years old, running around with shorts, often knee-high boots and a stick in the Brazilian Cerrado. At first we lived in tents, with a makeshift kitchen whose fire also heated water pumped in from the river. There were plant nurseries, big snakes and spiders, a cleared field for futebol and another that served as a runway for a sturdy aeroplane that was the only other way to arrive other than a two-day hike through wild savannah. The road to the nearest town, 40 kilometers away, would only be built later.

My father researched endemic plants of the region and eventually a house was built on the roof of which I laid down and gazed into the infinite night sky and the backbone of night.1

One day, upon dad’s return from a trip to another continent, I was delighted that he had with him a strange machine with faux-wood panels and a slot for cartridges. It was called an Atari 2600 Video Computer System, and he brought along a few games, including Night Driver and Space Invaders.

Days were spent outside walking in the forest, swimming in the river, observing and listening. I played and daydreamed. I learned about the Cerrado’s plants and creatures from an old man named Procópio who taught me to make rope from dried palm leaves, about the daily habits of animals, the insects and snakes that were dangerous, and the strong current and life of the river nearby.

(I recently found the house we lived in, and it saddens and angers me to see that after years of abuse of the land, the Rio Arrojado, and the cerrado around it, is dying. The war for water, as real as wars for oil and other resources, has arrived in Bahia.)

At night we would sometimes see a large snake with bumps all along its body — frogs it had for dinner — in the veranda outside, or caranguejeira spiders on the hunt. When my brother visited once he remembers playing Defender through the night and reaching 1 million points, upon which the score turned back to 0).

One day I arrived at and promptly walked out of what was to be my first school when I saw two nuns shouting at a young girl while holding her by the ear. Two years later in Brasília I did begin school, and was amused by some teachers’ attempts to encourage us to stand and put our hands on our chests during the singing of a song which sounded like something a military band would play.

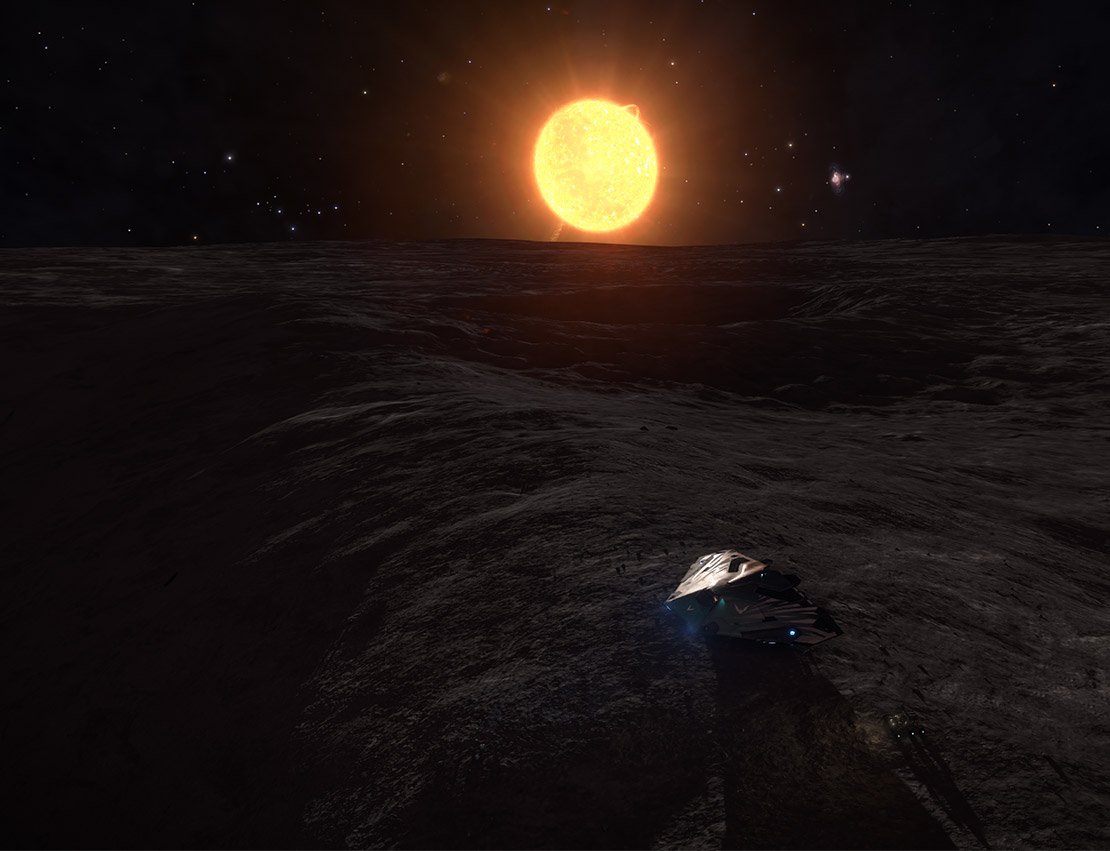

Now I live in a city surrounded by languages and people from around the planet we inhabit. Here I look for nature in the streets and a few parks, including a small forest called Inwood, though I miss the road and the landscape. I cannot yet return there in this world, so I return in computer games.

Note: Light was regarded formerly as consisting of material particles, or corpuscules, sent off in all directions from luminous bodies, and traversing space, in right lines, with the known velocity of about 186,300 miles per second; but it is now generally understood to consist, not in any actual transmission of particles or substance, but in the propagation of vibrations or undulations in a subtile, elastic medium, or ether, assumed to pervade all space, and to be thus set in vibratory motion by the action of luminous bodies, as the atmosphere is by sonorous bodies. This view of the nature of light is known as the undulatory or wave theory; the other, advocated by Newton (but long since abandoned), as the corpuscular, emission, or Newtonian theory. A more recent theory makes light to consist in electrical oscillations, and is known as the electro-magnetic theory of light.

Beauty improves life. When gray walls darken windows and waves from cars and motorcycles bounce in, one feels the urge to launch something heavy at the offending vehicles, as one’s father would have in his younger years.

Instead, one finds respite in virtual worlds. The headphones keep the unwanted pressure out, and along with the light, sound and motion one experiences a little of the environments we evolved from: space, the sea, the land, and the forest.

Tanoa jungle ambience in Arma 3 Apex, 2016.

We humans look rather different from a tree. Without a doubt we perceive the world differently than a tree does. But down deep, at the molecular heart of life, the trees and we are essentially identical.

The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.

We can’t yet, maybe never, live without our bodies, as we are our bodies. But we can travel back in time, and into the future, and communicate with those who came before us — and with those not yet born — through books, paintings, photographs, music, film, sculptures, buildings, websites and computer games — things we make with our hands, which may have given rise to our language, our tools, perhaps ourselves.

If there are frontiers between the civilised and the barbaric, between the meaningful and the unmeaning, they are not lines on a map nor are they regions of the earth. They are boundaries of the mind alone.

Is not the observer, after all, the observed?

-

I did not play the original Elite until recently, but did play Space War, on a IBM PC circa 1989. You can play both in a web browser courtesy of the Internet Archive. ↩︎

· ˖ ✦ . ˳

Come with me in creative journeys through music and play by subscribing to my YouTube and Twitch channels. ❤︎ Did you enjoy this post? You can buy me a moment of time.

Possibly Related:

˳ · ˖

Prior entry: Complementary books and video games

Next entry: The door